An Overview

In December 1989, I moved to Los Angeles and in July 2000, I went to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to do some technology work. This was a nice surprise, as most of my remote tech work was just that; remote and away from home. As we fly into or out of LA we can often see the Los Angeles Aqueduct and during my work at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power I asked one of the Engineers what would happen if an earthquake caused, let’s say a 30% reduction in the aqueduct flows; his reaction “You don’t want to know!”

The January Fires In LA County

As I create this article, fires are ravaging Los Angeles, I actually left LA in August 2014 to relocate to Eugene OR. Nevertheless, I do have family and friends there still and my years in LA were largely wonderful times in my Mexican family. Currently there is some controversy around a lacking of water for fighting the fires and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power were mentioned in a news piece I watched, yesterday.

The History Of Los Angeles & Water

Prior to the European incursions (more correctly invasions) into North and South America, what we now term “Indigenous Peoples” were already here. The Indigenous Peoples of the Los Angeles region had a cultural awareness of fires and referred to the area in ways that recognized its natural fire ecology. Before European colonization, the Los Angeles Basin was inhabited by the Tongva (or Gabrielino) people, as well as the Chumash to the north and west. These communities lived in harmony with the natural cycles of the land, including fire.

Historical Connection to Fire

The Los Angeles region, like much of California, has a Mediterranean climate with wet winters and dry summers, making it prone to wildfires; this climate is of course changing. Indigenous peoples understood fire as a natural and necessary part of the ecosystem. They practiced cultural burning, intentionally setting controlled fires to:

Reduce underbrush and prevent larger, destructive wildfires.

Encourage the growth of certain plants for food, tools, and medicine.

Maintain grasslands for hunting.

The use of fire was deeply tied to ecological stewardship, and this tradition of burning predates the current wildfire challenges exacerbated by climate change, land development, and fire suppression policies.

"The Valley of Smokes"

There is some historical evidence that indigenous peoples referred to parts of the Los Angeles Basin as a "valley of smoke" due to the frequent natural and cultural fires. European settlers later documented the smoky conditions, especially during seasonal burns. For example:

Spanish explorers like Gaspar de Portolá and Father Junípero Serra encountered a hazy Los Angeles when they arrived in the 18th century. They attributed this to fires set by the native inhabitants.

Early descriptions of the region often noted a constant haze, which was a mix of smoke from fires and marine layer fog.

This historical relationship between fire and the land is a critical piece of understanding the ecology of the Los Angeles region and the long-term challenges of fire management today.

Yes, the Santa Ana winds have been a natural phenomenon in Southern California for thousands of years, long before European colonization. Indigenous peoples, including the Tongva and Chumash, would have experienced and adapted to these seasonal winds as a part of life in the region.

What Are the Santa Ana Winds?

A primary cause or accelerant to the current fires are the Santa Ana winds which I experienced many times whilst living in LA. The Santa Ana winds are dry, warm winds that blow from the inland deserts (the Great Basin) toward the coast. They occur when high-pressure systems form over the desert areas, pushing air downhill through mountain passes and canyons. As the air descends, it compresses, heats up, and becomes drier. These winds are most common in the fall and early winter, although they can occur at other times of the year and they are often called “Devil Winds”.

Impact on the Landscape and Indigenous Life

Fire: Santa Ana winds were a significant factor in spreading fires, whether naturally ignited by lightning or intentionally set as part of indigenous land management. The winds could quickly fan flames, making fires much larger and more destructive.

Travel and Shelter: Indigenous peoples would have been aware of the challenges posed by these winds. They likely built their shelters and settlements with an understanding of wind patterns, choosing locations that offered protection from the strongest gusts.

Hunting and Foraging: The winds could affect hunting by dispersing animal scents and scattering seeds or plant materials. Indigenous people would have adjusted their activities based on wind conditions.

Cultural Understanding

The Tongva and other local tribes likely incorporated the Santa Ana winds into their oral traditions and spiritual beliefs. Natural forces like wind, fire, and water were often viewed as part of a living, interconnected system that shaped life and required respect.

While the Santa Ana winds are a natural occurrence, modern development has heightened their destructive potential. Dense urbanization and fire suppression policies have disrupted the natural fire cycles, making the combination of winds and wildfires far more dangerous today. Sadly we are currently seeing the consequences of this.

Post Colonial Developments In The Area

Here is a historical timeline of the Los Angeles area, tracing its development from the arrival of the Spanish through to its incorporation into the United States:

The Spanish Era (1769–1821)

1769 – Spanish Exploration:

The Portolá Expedition, led by Gaspar de Portolá, was the first recorded European visit to the Los Angeles Basin. Accompanying the expedition was Father Junípero Serra, who founded Mission San Gabriel Arcángel nearby in 1771.

Indigenous peoples, including the Tongva, were forcibly converted and relocated to missions, disrupting their traditional way of life.

1781 – Founding of El Pueblo de Los Ángeles:

Governor Felipe de Neve established El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula (The Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels of Porciúncula).

The original settlement included 44 settlers, a mix of Indigenous, African, and European people from Mexico. The area was part of Alta California, a province of New Spain.

1797 – Growth of Mission San Gabriel:

The mission became one of the most successful in California, producing crops and raising livestock, but its expansion came at great cost to the Tongva and other Indigenous groups, many of whom died from disease, forced labor, and cultural disintegration.

The Mexican Era (1821–1848)

1821 – Mexican Independence:

Mexico gained independence from Spain, and Alta California became a Mexican territory.

The missions were secularized in the 1830s, and their vast lands were divided into ranchos, large private land grants primarily given to Mexican citizens (often military officers or politicians).

1820s–1840s – Ranchos and Growth:

The Los Angeles area transitioned into a ranching economy dominated by cattle. Wealthy rancheros controlled the economy, and their estates became centers of power.

Pio Pico, the last governor of Mexican California, was a prominent figure from the Los Angeles area during this period, hence Pico Blvd.

1846 – The Bear Flag Revolt and the Mexican-American War:

During the Bear Flag Revolt, American settlers declared California an independent republic (briefly).

The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) led to U.S. forces occupying California. Several skirmishes occurred near Los Angeles, including the Battle of Dominguez Rancho and the Battle of San Pasqual.

U.S. Annexation (1848–1850)

1848 – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo:

The war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico ceded California and much of the Southwest to the United States.

Los Angeles officially became part of U.S. territory. Mexican residents (Californios) were allowed to remain and retain their lands, though many lost them due to legal and financial pressures.

1850 – California Statehood:

California was admitted as the 31st state of the United States.

Los Angeles was incorporated as a city on April 4, 1850, with a population of about 1,600. It began transitioning from a ranching hub to an urban center, though it remained largely rural for decades.

Key Themes in the Transition

Indigenous Displacement:

Both Spanish and Mexican periods saw the systematic displacement and exploitation of the Tongva people, whose population plummeted due to disease, forced labor, and cultural destruction.

Land Ownership Shifts:

The ranchos of the Mexican era gave way to American ownership as settlers arrived, and many Californios lost their lands through taxes, lawsuits, or outright confiscation.

Development of Infrastructure:

Under Mexican rule, infrastructure such as the Zanja system (a network of irrigation canals) was developed, laying the groundwork for future urban growth.

Economic Evolution:

Initially focused on ranching and agriculture, the Los Angeles area began to diversify its economy after becoming part of the U.S., leading to rapid urbanization later in the 19th century.

The Gift (Theft) Of Water

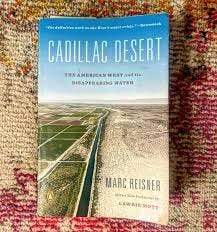

In Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner explores the history and consequences of water development in the American West, with a significant focus on the Owens Valley and William Mulholland, the chief architect of Los Angeles's water system. Here’s a brief synopsis of their role in the book:

The Owens Valley and the Los Angeles Aqueduct

Owens Valley: Once a fertile agricultural area east of the Sierra Nevada, the Owens Valley had a rich natural water supply from the Owens River. The valley supported small-scale farming communities.

Los Angeles’s Water Crisis: In the early 20th century, Los Angeles faced a growing population and a limited local water supply. The city needed a solution to sustain its growth.

William Mulholland and the Aqueduct Scheme

Mulholland’s Vision: As head of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, Mulholland spearheaded the plan to secure water from the Owens Valley to meet the city’s needs.

Deceptive Tactics: Using underhanded methods, including secretly purchasing land and water rights from Owens Valley farmers, Los Angeles secured control of the water. Many farmers were misled about the scale and intent of the project.

The Los Angeles Aqueduct (1913): Mulholland completed the 233-mile aqueduct, diverting the Owens River to Los Angeles. This monumental engineering feat, partly via the Mojave Desert, transformed the city into a booming metropolis but devastated Owens Valley.

Impact and Fallout

Environmental and Economic Collapse: The Owens Valley was left dry, its agriculture and ecosystems destroyed. Dust storms from the now-dry Owens Lake became a major environmental hazard.

Resistance from Locals: Owens Valley residents fought back, sabotaging parts of the aqueduct in the 1920s in what became known as the California Water Wars.

Mulholland’s Legacy: While Mulholland is hailed as a visionary who shaped Los Angeles, his actions also symbolize the exploitative and unsustainable nature of water politics in the West.

Relevance in Cadillac Desert

Reisner uses the Owens Valley as a case study to illustrate broader themes of greed, hubris, and the environmental costs of large-scale water projects. He critiques the short-sightedness of these efforts, highlighting how the pursuit of growth often ignored the long-term ecological and social consequences.

In essence, the story of Owens Valley and Mulholland exemplifies the central thesis of Cadillac Desert: water has always been a source of power, conflict, and exploitation in the arid West.

Conclusion (Back To The Future-Present).

Hopefully, during this article we have enunciated how the history of Los Angeles and area evolved.

Overall and most important of all, there is nowhere near enough precipitation (rainfall-snowfall) to support the current population of Greater Los Angeles and Southern California. Over the past decade, annual precipitation in the Greater Los Angeles area has exhibited significant variability, reflecting the region's susceptibility to both droughts and periods of above-average rainfall.

The National Weather Service reports that the "normal" or average seasonal precipitation for downtown Los Angeles is 14.25 inches, based on the 30-year average from 1991 through 2020.

However, yearly totals can fluctuate markedly.

For instance, during the 2022-2023 season, downtown Los Angeles received 28.40 inches of rain, significantly surpassing the average. The irony of this is that because LA is in essence a “concrete jungle”, getting water out of the streets of Los Angeles and into the Pacific Ocean was a big imperative.

In contrast, the 2020-2021 season recorded only 5.82 inches, indicating a substantial deficit.

This pattern of variability underscores the challenges in water resource management for the region.

It's important to note that while these figures provide a snapshot of recent precipitation trends, the region's water supply is influenced by various factors, including snowpack levels in the Sierra Nevada, groundwater reserves, and imported water from sources like the Colorado River.

Therefore, effective water management strategies must consider both local precipitation and these broader factors to ensure sustainability.

For a comprehensive record of annual rainfall in downtown Los Angeles dating back to 1877, you can refer to the Los Angeles Almanac's detailed compilation.

This resource offers valuable insights into long-term precipitation patterns and trends in the area.

Thank you as always for reading our articles, this is much appreciated.